Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 1 (2007)

- Jane Montgomery Griffiths

Jane Montgomery Griffiths

Jane Montgomery Griffiths talking with Lorna Hardwick about the Cambridge Greek Play

Jane Montgomery Griffiths, a Lecturer in the Classical Studies Centre at Monash University, is a specialist in Greek drama in contemporary performance and has combined academic teaching and research in the UK and Australia with professional performance practice as an award winning actor and director in the UK . She has taught in universities in both drama and Classics departments, including stints at York St John's and Bretton Hall University Colleges (the University of Leeds ) La Trobe University and the University of Melbourne . She has also held two visiting Fellowships at Cambridge University as the Judith E. Wilson Visiting Junior Fellow in Drama and the inaugural Leventis Fellow in Greek Drama, during which time she was Director of the Triennial Cambridge Greek Play. She holds BA Hons./MA degrees from the University of Cambridge and a PhD from the University of Melbourne

The following is a transcript of two interviews recorded with Jane Montgomery at the Open University for the Reception of Classical Texts Research Project. The first interview took place at an early stage in Montgomery’s thinking about the 2001 Electra production. The second interview was a post-production response, which documented her reflections on the experience.

- A PDF version of these interviews is also available

Interview 1 (22 May 2001)

LH. Jane, could you tell me how you first came to get involved in the Cambridge Greek play?

JM. I was a student at King’s College, Cambridge, about twelve years ago, studying Classics and I wasn’t involved as a student actually in the Greek play. There was quite a bit of anti-classicists prejudice amongst the student Thespians, and we very unfairly dismissed the Greek play as being about sheets and safety pins, partly based on the very dim memory of seeing one several years before, which was maybe not the best production I have ever seen, and I had just been involved in what was then the Cambridge Classical Film Unit’s strange black & white movie, The Bacchae, directed by Andrew Bamfield. So, when it came to the Greek play in 1989, Dictynna Hood was doing The Bacchae and I thought, well, you know – already done it once, so not again. But I watched it. I went to see it and I was astonished by it. It was a wonderful performance, very, very, well directed and I remember sitting there in the Arts theatre thinking, damn! I really should have been involved in that, that was very good. So then I disappeared off to be an actress for six or seven years and got a phone call, sometime during 1995, from Simon Goldhill, who was my supervisor at Kings, asking me to apply to direct the 1998 production. I applied first to do Electra, and was told to come back with another play I went back with Trojan Women, really out of desperation because I couldn’t think what else to do. I remember at the committee meeting being asked to come up with some ideas for the staging and I didn’t really know at all at that point what I thought the play was about. I had vaguely thought that I wanted to do something about shifting environments and unstable settings. So I had this idea for an absolutely massive, huge, big industrial block of ice that would melt onto sand throughout the whole show, so that what they thought was stable sand, would turn into mud by the end, which if you say to a production manager, they’ll start twitching and say ‘Have you thought about the Tec? How difficult it’s going to be to time this?’ I was offered, and accepted, the job in 1995 while I was still a resident actor and associate director at Harrogate Theatre so I started talking to one of the designers there called Michael Spencer. Michael works in a very post-modern way, I think, as a designer and the two of us together started to brain-storm ideas and we kept having this idea of wanting an environment that you think is stable but then shifts. So we played around with all sorts of ideas about something that would convey subverted expectations and eventually we came up with a swimming pool. The idea, that, you know, several years before you could put kids laughing and playing with bouncy balls there, but you drain the swimming pool and you start to see the nasty bits in the corner, and you murder a lot of people in the swimming pool and you get even nastier bits in the swimming pool and you chain a load of women up in the swimming pool and it’s a very, very, unpleasant environment. We then took that idea and elaborated it and tried to, with all of the characters, all of the costumes - the entire design - look for something which was going to be culturally significant. Either it signifies that in our culture we could appreciate but then they could be twisted and subverted because the one thing we didn’t want to do was something which was overtly Greek – sheets and safety pins. Not because I’m particularly against that, and I know it sounds disparaging saying sheets and safety pins and that’s actually the professional actor’s prejudice, more because it’s such a great opportunity to explore a play like this you might as well start to experiment with different things. So, the Trojan Women happened in October 1998. We changed the format – usually the Greek play happened in the March of each year, which meant that there were only two to three months in each year to rehearse it. I was very keen that we got good actors, rather than classicists, so we changed the date to have ten months to rehearse. Out of the cast of fifteen only five, I think, spoke Greek. The rest we taught the Greek from scratch making sure they actually understood it rather than just reciting parrot fashion. This process is being repeated now in 2001, where finally I get to do Electra. Yes… it was again vetoed, by the same member of the committee, who thinks I am mono-maniacally obsessed with the play and that I should not be allowed to do it. He’s come round, but the other option I gave them was the Andromache which I’d also love to do, but various members of the committee thought it was a rubbish play, and so it wouldn’t go down very well.

LH. What attracts you especially to the Andromache?

JM. I think it’s such a peculiar play. It’s so fascinating. To me it’s got the peculiarities, the tragedy and the comedy of something like Pericles, with the late Shakespeares. I think it’s a very beautiful and a very brutal play all at the same time. I love, I’ve always loved, the character of Andromache you know, ever since reading the Iliad, she’s such a gorgeous women. And her predicament at the beginning of the play is as heart rending as anything I’ve read in Greek drama. Then you have the wonderful, political, polemical, sophistic debates about ownership with Menelaus. And of course it’s all about let’s bash the Spartans, a whole load of Athenian propaganda. Then from that it moves into this beautiful, bizarre, dream play. So I wanted to do it, and I still want to do it, for its oddness. I don’t know how I would do it – I have absolutely no ideas – sort of just trust the play that you’ll get the ideas eventually. But understandably, the Greek play committee, although they're very generous with experimental directors, also need to appeal to schools’ audiences and as Andromache is never a set text , until we’ve got a large audience base, it’s worthwhile going for the better known plays.

LH. I’m interested in what you say about the audience base, because there are quite a lot of recent examples of companies who have started off knowing that they have to appeal to the schools audience, you know, have something which is a set book, as it were. And they have either developed from that, or they have gone under because they can’t produce something which is going to attract teachers to bring their students. Now, isn’t there an argument that the actual historical and cultural status of the Cambridge Greek play, actually does give a very firm base, that people are going to come anyway, and that therefore to use that as a springboard for more experimental work or lesser known plays, might be a real possibility?

JM. Oh, absolutely, you’re completely right, that’s why they allowed the Trojan Women for instance. And also because in the 121 years of the Cambridge Greek play the Trojan Women had never been done. Unfortunately, because of some problems with the Arts Theatre which at backstage was going through a real upheaval, we were scheduled in the school half-term. So immediately our audience base was… well, it was far more than decimated. We were expecting to play to seventy – eighty percent houses, and ended up playing to, I think, forty-five percent. We simply didn’t have… the schools weren’t there. So, we needed to come back from that. It was a great shame with the Trojan Women, because artistically it was a surprising success for everyone. I don’t think anyone really expected it would go down so well. At various points I did expect to be lynched, actually, because it was a big, big, change in artistic direction for the Greek play. I don’t think it’s playing safe at all by going for something as well known as Electra, and particularly not the way I’m approaching it … but we’ve made sure the schools are coming, and in fact for the first time we’re trying an outreach programme, whereby the schools book tickets for the play, I go to them and give them a free workshop. And this isn’t just about wanting to get bums on seats, it’s actually something that I feel really passionately about – that if you want to get the next generation coming to see Greek plays, especially non-Greek speakers, you’ve got to realise there are other ways to appreciate it. Just like say, the outreach programmes that the Royal Opera House are doing at the moment, which is very exciting. Why not do a ‘Bollywood’ tour? So great, its got a lot of Southall kids coming to opera. And that’s, sort of, how I feel about the Greek play. Some of the pick-up, I mean it’s to be expected, that many of the schools who have taken up the offer, would already be coming anyway. And we haven’t quite had the non-Greek speaking, non-classicist drama school base which I was hoping for, but we’ve still got a bit of time to work on that. My aim is to have as many English students, drama students, Classical Studies students as Greek speakers.

LH. I want to explore for a minute, this apparent tension, between the fact that you’re doing a play in the original Greek and yet in the approach to the play, the staging, the design and so on, you’re doing something, which is, it seems to me, sounds as though it’s going to be very far from an archaeological reconstruction of how it might have been, etc. Do you think that presents particular difficulties, or opportunities? How do you see that contributing to public perceptions of what Greek drama is about?

JM. To me, it opens up massive areas of freedom. I – despite my classicists training – I can see absolutely no point in trying to have an historical reconstruction. You know, even something like the Peter Hall Oresteia – of course it wasn’t an historical reproduction. You know - great, you’ve got masks, you’ve got rhythm and it was very exciting but it’s not how it was done two and a half thousand year ago. So why should I try to do the same now? My aim is to try to find a coherent theatrical vocabulary for the production, which is going to be a very different theatrical vocabulary from the Trojan Women or from, indeed, the Electra I was in as an actress two years ago. I mean completely different, couldn’t be further. I am aware that in some respects we’ll be throwing some things, some of the babies out with the bath water with this Electra because I’m very interested in making it a memory play, almost a dream play. So, maybe we will lose some of the political content of the play, and it’s possible we might lose some of the gender content, but we will also, hopefully, gain other things. I would just like audiences to be able to come along and think, OK this isn’t my Electra, but it’s an Electra and it’s kind of interesting. It’s the old thing, you know with actors and also directors, they don’t mind if you love it or hate it as long as you don’t have a bland response, and that’s how I feel about it.

LH. When you say ‘theatrical vocabulary’ what kinds of thing have you got in mind? What kinds of communication are involved?

JM. For this play, for the first time we are …the first time I’ve ever done it anyway… it’s relatively multi-media. We have large plasma screens which will be, from time to time, showing video of Electra’s memories. Not actually for the audiences’ benefit, but for Electra’s benefit. I can see no purpose for the chorus in this play, apart from as adjuncts to Electra – almost as part of her bi-polar personality. Every time she looks at the chorus she sees what she could have been. Almost like a sister. Somebody who is moderate. Somebody who doesn’t have bruises all over her because if you compromise then you’re OK. And I’ve just noticed this movement in the play: that every time Electra almost calms down, the chorus says something, with the voice of moderation, that gets her going again. That made me think - what if the Chorus is actually a meta-theatrical illustration of Electra’s schizophrenia? So they can manipulate the video screens to force her to recognise her memories. Now, this is a really dodgy and potentially very dangerous, and also a really naff, idea and we’re very conscious to try not to overgild the lily. I mean we’re at the stage of rehearsals now, where it could be disastrous. It could be brilliant – I don’t know, but I think it is worth exploring this, because I don’t otherwise know what the chorus is doing in that play for us now. It’s not the same as it was in Sophocles’ days. I was in the Deborah Warner production, as understudy and then in the Chorus for a while and I remember being in the Chorus and none of us actually knowing what we were doing. Now, that production was one of the most brilliant plays I’ve ever seen. I thought it was stunning, a definitive production of the play, to some extent. But the Chorus, for those of us in it, didn’t work at all because we didn’t exist - we’re not characters, we’re not functionaries. So I want to try to do something different with the chorus. Now of course that changes the entire theatrical vocabulary. So, instead of it being a naturalistic piece, it’s overtly meta-theatrical. That’s aided by the fact that this time, for the first time in the Greek plays’ history, we’ve got surtitles above the proscenium, but we’re also hoping to have surtitles actually on the stage in Greek going on at the same time. So you get the idea that you have different levels of framing and different levels of mimetic reality. And that’s an interesting one, mimetic reality, that you’re both inhabiting the moment as a real person but also interpreting it and representing it, as the audience is of course. So, the theatrical vocabulary of it, certainly for this play, is based in probably, post-modern performance de-construction. Now, having said all that, I think it’s absolutely crucial, that we get to the core of the play, which is one woman’s suffering. Without that there’s no point in the play and the thing I kept…. before we had any ideas about the video screens or the memory the thing we came to was that this was a woman being vivisected for our pleasure. So the integral… the only really essential part of the set, is the Petrie dish that Electra inhabits for the entire play. Because it’s like you’re taking a knife and opening her up and just when you think the wound is going to start healing you open it up again a bit more – and that’s the whole play. So, it’s going to be quite challenging, I think, to work out exactly how to view this play.

LH. You referred just now to your own experience as an actor, as well as a director, and I’m very interested in that for the implications of how you work with your cast, how you conceive of the performances emerging. Do you see it as some kind of co-operative, interactive process? Or do you stand aside as Director? How do you approach it?

JM. Oh, it has to be co-operative. Absolutely. The great thing about having been in a chorus is I know personally how awful it is to be in the chorus. Even if it is a brilliant performance, brilliant production. So I’m very, very, conscious of trying to make the chorus feel as valued and as integral to the piece as, say, the actress playing Electra. Now, the other thing about playing Electra of course is that I’m very worried about this poor actress who’s having to go through this experience. When I played her, I had bruises all over me for six months, I lost two stone, I was in a right old state. As a director and also as a tutor, because I’m dealing with a student cast, I don’t want this young woman to go through that process – I want to look after her – but I’m also aware as an actor, that you sort of have to. So, it’s a very delicate balance. The thing I don’t do, and I will never do, is say well actually, at this moment, you should be thinking this or you should be doing that, because they have to find their own route. I might be able to guide, I mean for instance, just the other day we were in rehearsals, and I had to stop and say just take your shoes off for a minute, because actually being barefoot will change this entire scene for you. And it did. There’s something being rooted to the ground. But that’s sort of as far as it goes. And we work in a way that is both very textual but also quite method based to try to get them really inhabiting the parts. The actress playing Clytemnestra, who is a Mycenaean Linear B scholar, which I love, was saying the day that actually she is going to find just doing the play frustrating, because they’ve done so much character work, on say the relationship between Aegisthus and Clytemnestra, that the fact they never meet on stage is really going to bug her. Of course that’s great, I really like that. It’s just how to channel that so it doesn’t go off the rails. So you know, when somebody walks on stage, they have a complete history behind them, but that’s not what you see, you see the text. There isn’t a moment, other than what’s happening in the play.

LH. The other point I’d like to take up at this stage, is to ask you about what you said about the meta-theatrical aspects of your work on the play. You said that a significant proportion of the audience were probably going to be school students who perhaps are not particularly experienced as audiences and haven’t studied a great deal in terms of theatre. How are you going to explore these meta-theatrical aspects without perhaps in a sense manipulating your audience, and that’s putting it crudely?

JM. The issue of manipulation is very interesting because I sort of wonder whether it’s possible for any actor or director not to manipulate and audience, whether it be consciously or not. The music has to play a big part in bridging the gap between the audiences’ expectations and the actual experience of being part of what is both a theatrical and a meta-theatrical process. I would probably not do this at all if it were in English. I would probably have a completely different idea about the production. The point is here, that if you are doing a production that is in a dead language, which very, very, few people are going to understand, that makes it meta-theatrical in its very form. People don’t understand it in the same way, so I think the more ways of decoding the sign system the better. Now, it might be that some people pick up on some things and not on other things, and I’m hoping that it will be… and we’ve got a good enough actress playing Electra that actually you will very quickly forget about the trappings. They’re not trappings – they are ways of turning the screw on her. None of these is being done with a sort of Hey look at me, I’m a great meta-theatrical director, at least I hope it’s not, that’s not what we’re intending and I would be really worried if that’s how it came across because everything on the outskirts of the Petrie dish, which is the real world of the play, is there to underline what’s happening in the Petrie dish. So, I’m hoping for schools’ audiences – they will understand the story, they will pick up on the emotions. But they’ll also hopefully think that’s interesting, there are other ways of approaching a text like this, and that actually the only limitation is your imagination. I’m also expecting there will be some initial confusion. But this is the interesting thing about the experience with the Trojan Women. One or two schools’ parties did manage to come, despite being in the holidays, and we had Cassandra coming in, at the back of the auditorium on a trolley, in a wedding dress cum straight jacket pulling behind her a six-foot blazing wedding cake. And we were just waiting for the laughter, you know and that was followed by Andromache coming in dressed as Doris Day, and we were just waiting for the guffaws. Never once. There wasn’t a laugh from any school party at any schools’ matinee. And I think that there’s something so … I spent a long time thinking about that. Why did that happen? Why didn’t we get the laugh? Because I’d said, get the laugh, use it, subvert it. But it never happened. I suppose it’s because it’s so unexpected. You don’t think anyone is going to be stupid enough to have a six-foot wedding cake coming into the Trojan Women. When it does, that takes you so long to get used to it that by then you’re actually in the scene then anyway. So I’m hoping when they have six chorus members dressed in 1930s ball-gowns coming on the same process is going to happen. I don’t know, we’ll have to wait and see about that one.

Interview 2 (21 February 2002)

LH. A striking Feature of the production was the video screens (e.g. with footage from Orestes' childhood). What factors influenced you in including these and how did you select the material to be shown?

JM. The video use was a 3-pronged idea. The first thoughts came from when I'd been acting Electra in '99. Part of my character preparation was imagining certain scenes/memories which repeated endlessly in my/her head. They ended up becoming a type of acting short-cut to get me into character quickly. Back stage, or during certain moments during the play (notably the Tutor's speech) I could switch into an imagined scene/memory and use the image to kick-start a new chain of emotion. Occasionally the order of the scenes would change in my mind - one night I might focus more on Orestes, one on Clytemnestra - but the specifics of the replayed scenes were the same… and were accompanied in my mind by either the sound of a 78rpm record player in the next room playing Strauss waltzes, or Britten's arrangement of 'O Waly waly' - something about their plaintive sentimentality I guess - can't think why else as the choice now seems pretty arbitrary. Later, as a director when I started preliminary design meetings for the play, I wasn't sure whether there was any mileage at all in using the replayed scene idea…. after all, it'd been an acting tool and was a very private process. An I felt it essential that the actress playing Electra should be able to make up her own world and develop her own character short-cuts - she didn't need my imagination foisted on her. But, despite my initial doubts, Michael Spencer [the designer] and I kept coming back to the idea of the repeated images. The circularity of the images, their repetition, the specificity of their gnawing presence seemed to sum up exactly Electra's predicament… constantly replaying the same images, day after day - self-perpetuating her death-in-life and life-in-death existence. And there is also something very odd about time and Electra's perception of it in this play - time for her is synchronic and diachronic, endless and instantaneous - just the sort of temporal distortion that happens in film… Michael was initially quite keen on having a split screen taking up most of the set, simultaneously showing repeated memories and Electra on stage as if caught on a security video [these discussions started in '99, just before the RNT's Oresteia, and there's an interesting coincidence in his initial vision of the use of video]. But we couldn't find the logic to the dual use: two very different metatheatrical devices and purposes that just didn't make theatrical sense for us. The logic came with the development of the chorus. We had discussed many different approaches to the chorus, and from day one agreed that they could not have any vestige of naturalism - they had to be simultaneously metatheatrical in terms of the production, and part of Electra's psyche in terms of the characterisational 'reality'. So, they became 6 china doll versions of Electra, or rather her internal Furies, or her super-ego, or her imagination of herself on the night of Agamemnon's murder …. which actually all amount to the same thing for her. There's an interesting thing in the text: every time Electra just starts to calm down, the chorus manages to stoke her up again with insulting Job's-comforter platitudes or with reminders of just how unfortunate her lot is. We though if there is any mileage in the videos. It'll be as part of that - the chorus rub salt in the wound) or perhaps scratch the scab, by manipulating the images which goad Electra (if you like, just as Electra's super-ego reproaches her, dragging her further in self-harm in her endless replaying of corrosive memories). The chorus are for her and of her, and their manipulation acts as a prompt to make her remember and an aid to reinforce the image.

As for the choice of scenes, they were visual representations of what Electra actually describes in her lines - So we have Agamemnon as the best of fathers (waltzing with the little girl Electra on the beach), Orestes ‘her darling’, ‘blazing like a star’ (as the six year old boy play acting at being the hero), the night of Agamemnon's murder (the blood trail leading to his foot), and then various images of Clytemnestra the whore/mother-no-mother (in bed with Aegisthus/reclining on the beach, years before the murder but just as indifferent to Electra) and her and Aegisthus' humiliation of Electra (the post-coital lovers gloating over her). The feel of them was to be home-movie (early colour super 8) for Orestes and Agamemnon, and something much more cold/peculiar for Clytemnestra (in the end, Andrea Zimmerman, the video artist who recorded and edited the footage, rendered the Clytemnestra scenes to mirror and pulsate). Each scene was cut with other scenes to provide the sequence of images recounted in the text.

As is ever the case with these ideas, we ended up using less than we had originally anticipated. I'm a bit wary of the over use of multimedia in plays, and was determined to preserve the internal logic we'd found for their use. Consequently, we concentrated on the video screens only at very specific moments of the play when the pressure on Electra's imagination and memory was most extreme, and always tried to abide by the logic that they can only be used when there is a specific manipulatory reason for the chorus to show Electra the image.

LH. What factors governed the staging of the Chorus? E.g. numbers, pose, movement, costume?

JM. Well, the first problem with this play is ‘Who is the Chorus?’ . I was once in the chorus of this play, and it was extremely difficult to find any 'reality' to hang on to as an actor. Unlike the eponymous Euripidean choruses, these chorus women have no identity and no happy correspondence to the theatrical world of the play. Their contribution is peculiar, and if the general critical assumption that they are there to provide paramuthia (consolation) for Electra is all there is, the chorus become a relative insignificance. If that's the case, that their sole purpose is to give the heroine comfort, not only are they dull, but, it has to be admitted they are not very good at their job. Each platitudinous word of comfort they give either goads Electra to further rage or prompts her to fall into a despair of self-hate at her shamelessness. Add to that the very peculiar alienation of the choral stasima, and you're left completely uncertain as to who or what this chorus is all about.

So I decided I had the stark choice of either cutting the chorus or altering my perception of them. Very early on, I went for the first idea. I liked the idea of Electra speaking their lines to herself (a bit like the Jonathon Pryce' Hamlet, I guess, when he disgorged the voice of Old Hamlet), and replaying choral odes on an old gramophone. But relatively early on I realised that those were ideas that just would not work in this production, and that the physical presence of the chorus would add immeasurably to the theatrical world of the play. So, Michael and I started working out how they would be if their Job's comforter role was taken to metatheatrical extremes. After playing around with various Kafkaesque possibilities that were all discarded for being either meaningless or poor imitations of Robert Wilson, we clicked that of course the chorus were Electra and she was they - 'mirror, mirror on the wall', or an even more twisted take on Dorian Gray. So, as explained above, they and Electra were dressed in identical pink silk dresses (Electra's first ball gown, put on especially for Daddy's homecoming from Troy, and the chorus image preserved how Electra looked just before Agamemnon's murder, while Electra herself was in the humiliated present, wearing the same dress 12 years of suffering and degradation down the line. Crucially, only Electra ever saw or interacted with the chorus - they were entirely metatheatrical - necessitating some small adaptation of lines. As for the practicalities, the number of chorus - 6 - was dictated by the set and the sight lines of the Arts Theatre, and it turned out to be the ideal number. It meant there could be an interesting dynamic between them, without crowding or conversely isolation.

Blocking and movement style and patterns came mostly from the rehearsal room floor, and from the admirable experimentation and adaptability of the chorus. I was asking of them a very difficult acting exercise. Not only had they the difficulty of the music, the Greek (five out of six didn't know the language), and playing metatheatrical constructs (never an easy thing at the best of) but I was asking them to develop their own patterns of movement. Early on we had had some waltzing classes and I'd asked them initially to model their movement on Viennese waltzes, done with excruciating slowness. Once we hit the blocking stage, I gave them certain provisional starting and end positions, some specific cues for turning video screens and occasional synchronised gestures (like dropping their dolls at the news of Orestes death, or the unison blood-letting movement), and let them get on with it, asking them to experiment as they felt the urge during the rest of the scenes. Gradually as the episodes took firmer shape, I was able to concentrate on watching the chorus's physical improvisation and hone what worked and discard what didn't. we ended up with something that was deliberately alienated and alienating; as witnessed by some of the audiences' confusion with the concept. Interestingly, several members of the audience took them to be Geisha girls, which bemused me as the thought had never crossed any of our minds - but it was perhaps a significant observation. Their absence of individuality and cosmetic over feminisation, both inscrutable and disturbing - 6 images of Daddy's little girl; innocent but sexual; as hard and as fragile as china.

LH. Were there significant ways in which the staging changed or developed during the rehearsal process?

JM. Michael and I had decided on the general shape of the design about a year before rehearsals began. This time frame is a real luxury and accounts for the very few changes that happened during the rehearsal process. The biggest problem is always the practical/financial, and Michael and I were slightly prevented from realising some of our design ideas by the very basic and very insurmountable issue of performing in a proscenium arch theatre. Nevertheless, by the time the company came to approach rehearsing in the mark-up, we were very comfortable with the basic shape, and the only change we needed to make was cutting the original 4 monitors to 2 because of space and sight lines.

The staging is an interesting question. Looking back, I don't know that we ever really blocked the play. Put actors on that set, with that play, and there are only a finite number of combinations of movements. I work from the actor's perspective and by and large believe that if an actor knows their character, they will know where to move. So really, the only major directorial development was realising the need for stillness in many of the scenes. After some experimentation, it became clear, for instance, that Orestes and the Tutor need hardly move at all during their first scene, that there is a very still simplicity to the aftermath of the recognition scene that is counterpointed by the extremity of Electra's lyrics, that with all the scenes, again and again, the less we did, the better it was (…and thinking back, the most common note to the cast was to stop acting). The discoveries came in the chorus work, and repeatedly in the character discoveries came in the chorus work, and repeatedly I the character development. Since acting myself in the play a couple of yeas before, I'd had ideas I'd wanted to try out with characters. Some of these worked, some didn't. It was great fun, for instance, to play about with Chrysothemis's 'breakfast to go' in the first scene, but it didn't work for Clytemnestra to stub out the eyes on Agamemnon's photo with her cigarette. Whereas her burnt offering of banknotes to Apollo worked, her offering of her wedding trousseau to Agamemnon just didn't. Other 'props business' altered as rehearsals progressed: Orestes' hip flask turned into a receptacle for blood-offerings rather than whisky and Electra's tin of mementoes took on a life of its own. There was a great deal of specific characterisation work with the actors, but very little 'staging' ... perhaps the only exception to that was the development of the doll props for the chorus, which required occasional bursts of quite careful blocking.

LH. You decided to have surtitles. How did this decision affect other aspects of the production? (e.g. especially non-verbal aspects of communication)

JM. I'm still unsure about the surtitles. They are a massive boon/safety net for the audience who doesn't know the play (were sold out for six of the eight performances, and many audience members said that the surtitles were a crucial factor in their deciding to book), but I do feel that some of the immediacy, viscerality, sheer theatrical force of the Greek, they play, the experience is lost by having the extra framing device to hurdle. Now I love this play, and I was proud of the production, but even I felt curious alienated watching the show in a way that I haven't with other plays I've directed. Retrospectively I wonder whether the surtitles had something to do with this distancing … something lost in the translation. Do you, as an audience member, allow yourself to surmise meaning and thereby develop a new form of theatrical perception and understanding when you have the easiness and security of a simultaneous translation offered? We didn't, translate Trojan Women, and the audience response was more immediate - they were forced to connect to the internal rhythms of meaning, conveyed purely by sound and gesture. But then again, Electra is such an odd play - no easy ending, no catharsis (well, you could say that about a lot of Greek tragedies, but this one is particularly odd)… perhaps the alienation is right for this play. Ultimately, I was left feeling that the surtitles worked well in this production because of the metatheatricality of the play and our interpretation but that it wouldn't work so well on, say, Hippolytus or Hekabe, or indeed, an Electra which was more 'traditional'. It'll be very interesting to see what happens in the next Triennial.

As for any directorial decisions that came from the surtitles - well, the main one was an idea that in the end was just not practicable, to have a second sur-title box actually on the set [above the palace entrance] with stage directions and snippets from the play flashed up in ancient Greek. Sight-lines, software and finances made that impossible - a shame: I'd have loved it. The actors of course ignored the surtitles (although were some amazed to hear audiences responding to the specific ironies of their lines), and the only difficulty was synching the software to the action. Incidentally, the sight lines at the Arts are such that there will always be three entire rows unable to see the surtitles. We were eventually able to give those rows simultaneous audio translations … I'd be interested to know the relative, qualitative difference in having surtitles or audio description in terms of making the audience alienated from the action.

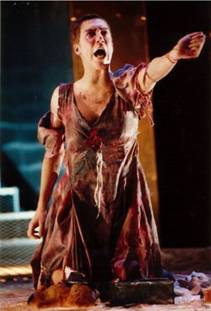

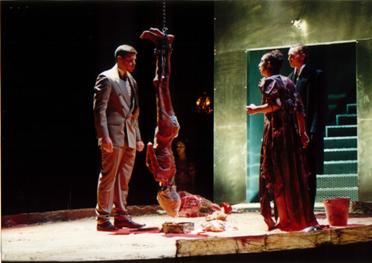

Images from the Cambridge Greek Play production of Electra, 10-13 October 2001, Arts Theatre, Cambridge, UK.

Electra (Marta Zlatic)

Electra and Orestes after the murder

Electra, Aegisthus and the hanging skeleton of Agamemnon

Find out more...

The 2001 production of Electra was followed by a conference: Complex Electra, Peterhouse College, Cambridge, 13-14 October 2001). For the selected proceedings see Didaskalia 3/5, 2001, at www.didaskalia.net.